Gaisuiliu Charenamei

Centre for English Studies, JNU, New Delhi

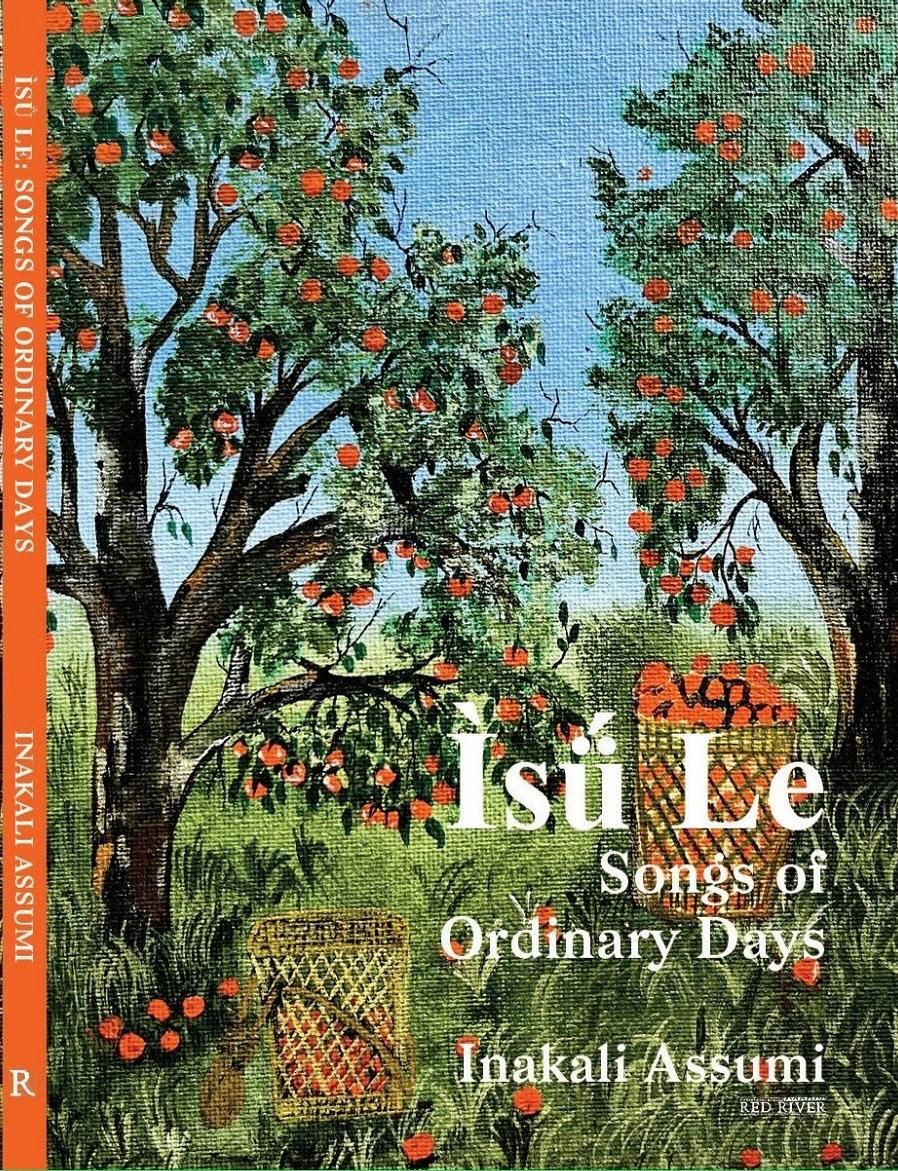

Inakali Asumi’s fifth book, Ìsǘ Le: Songs of Ordinary Days, is a collection of poems inspired by the passage of time within a single day. The collection is made up of three parts, each named after and representing the different parts of a day. The first section is “Morning Songs”, the following is “Afternoon Songs”, and the last section of the collection is “Evening Songs”. The author, Inakali Asumi, belongs to the Sumi Tribe found in the state of Nagaland. Asumi’s intention with this collection is to continue a legacy left behind by her people. The author’s foreword reveals the inspiration behind the title and the poems of this collection. The title of this collection is derived from a Sumi Oral tradition, folk songs inspired by the mundane and sung daily as a collective action. The songs sung by the Sumi forefathers were known as Ìsǘ Le, which, when translated into the English language, means “this morning’s songs”.

The poems have no names but are rather titled by the order of their appearance in roman numerals. The collection is made up of 51 poems. The first poem, “I”, begins not as an ode to the morning, but as an ode to the memories made in her youth.

The poetess describes the Sundays of her childhood. Here, the natural elements of the sun and the morning do not form the central focus of this poem but rather aid in the formation of a scene. The scene that is created before the reader is a collection of memories, almost as if the reels of memories presented before the reader act as a stand-in for the physical photographs taken by her father. It is made clear in this poem that the morning songs are intended to evoke a certain emotion, almost as if feeling a warm ray of sunshine on your brow.

But not all mornings are warm or pleasant. “XII” is a sombre poem about a morning without the sun. The morning sun is not just a tool that makes a Sunday morning photograph possible, but is rather a crucial element of the morning, without which the morning is unable to bring promise of hope and warmth. The narrator of “XII” wakes up to an absent sun and is immediately struck with grief. The absence of the sun is almost symptomatic of an air of death; the narrator finds no sign of life, because the sun has taken with it even the chirping birds.

Just as the mortal body ages by shrivelling into itself, the narrator fears that the sun has met the same fate. The possibilities of a new morning are juxtaposed with a morning where the sun’s presence is no longer guaranteed. The mornings, too, are subject to change, not unlike the passing seasons and months.

The second section of the poem is the Afternoon songs. The first poem of this section also begins with a mention of the narrator’s father. The poem makes no mention of the afternoon in the first stanza; it begins by adding context to the afternoon’s events. The activity in this poem is the narrator’s father going out to buy watermelons, but the tension and meaning of the poem are found not in the activity but in the discussion around it.

My father loves watermelons

but he calls them cucumbers.

He just wouldn’t agree

that watermelons are not cucumbers

and cucumbers are not watermelons.

The poem follows an interesting debate between father and daughter. “XXV” is a poem about a deceivingly simple disagreement between a parent and a child, but the last paragraph reveals a final layer of meaning. The narrator’s father’s insistence on the misnomer can be read almost as a resistance; it is a desire to hold on to his mother tongue. Perhaps in some ways, his insistence on calling a watermelon a cucumber is an act of remembrance, a nod to a simpler time. His affection for his language outweighs his fondness for the fruit.

But we don’t have a word for watermelon

in my mother tongue.

We call them cucumber

in my mother tongue,

my father replied.

Just as his child holds onto memory, the narrator’s father also holds on to his childhood. In this way, language and vocabulary too become a repository of memory and the passage of time. The poems of the Afternoon Songs reflect a stage in one’s life where one has crossed into adulthood but is unable to reconcile with the loss of one’s childhood. These poems reflect a curiosity and joy for life that are criticized when one is expected to behave as an “adult”. In the poem “XXXIII”, the narrator’s question into the bird’s thoughts is unappreciated by another adult. Matters of nature and a general sense of curiosity are seen as “childlike”.

In an attempt to focus on the larger and more serious problems of life, the small and the mundane are often left ignored. The conversation shifts to the “greater things” as the narrator learns to quieten her curiosity. The bird, which could possibly be a symbol for the larger natural world, is relegated to a world of no meaning- their capacity to think is taken away. The consequences of losing one’s curiosity do not take place within one’s mind but become a threat to the bird’s capacity for knowledge. The theme of growing pains continues till the last poem of the second section. The poem “XXXVI” also deals with the narrator’s curiosity. In this poem, too, her questions are left unanswered, not because they cannot be understood but because her questions can only be answered by time.

The narrator compares her body to her mother’s, and receives no reply other than her mother’s knowing smile. The narrator’s body is yet untouched by the marks of womanhood and motherhood, and her young mind is unfamiliar with the transformation her body will undergo. The young narrator’s questions are marked by a sense of genuine curiosity; she does not fear the differences in their bodies, nor is she repulsed by them. The ageing of the female body is presented here with neutrality, a simple acceptance that time brings change.

The final section of the poems, the Evening Songs, begins once again with a mention of family. While the first poems of the previous two sections featured her father as the centre, this poem follows a conversation between the narrator and her sister. The subject of “XXXVII” is the differences between the two sisters.

In a similar vein as the last poem of the previous section, this is a poem that celebrates differences. The narrator constantly finds herself alone in the shape of her thoughts and the interests of her heart. The narrator admires the moon, but her appreciation is cut short by her sister’s distrust. The poem ends by bringing the focus back to the bond between sisters. While one sister is more romantic, the other is more cynical, but ultimately the two bear the same roots. The idea of roots and a shared history is found once again in “XL”. In this poem, the choices one makes as they prepare dinner can be a link to their forefathers. Although the world they share is no longer the same, the inherited recipes remain unchanged.

In this poem, a separation has taken place. The narrator has now left her parents’ side. Her recipe is a bridge, therefore, to both her distant forefathers and her parents. The meal she plans will act as a bridge towards the home she has parted from. The Evening Songs seem to be poems in which the narrator looks for signs of home in an unfamiliar setting. The shortest poem of the collection, “XLII”, is a poem about the everyday reminders of home.

The short and terse tone of this poem is unlike the others within this collection, but it is in the dearth of words that the depth of emotion is made clear. Similarly, the last poem of the book, “LI”, is a relatively shorter poem in which the narrator’s joy seems to have run dry. As in the first section of the collection, the absence of the sun creates an almost liminal space where time and space are hazy concepts. However, even in the absence of light, the narrator continues to have a capacity to ruminate and ponder. The curiosity that she had to quieten is let loose in the temporal space of the night.

The final poem echoes back to the memories of the first poem, but the narrator of the final poem is a changed person. The warmth of the first poem is absent, and is replaced by a chilling stillness. But hope is not yet lost, as long as the narrator is in possession of her memories, there continues to exist the possibility of hope and regeneration.

Assumi’s Ìsǘ Le: Songs of Ordinary Days follows the growth and transformation of the poem’s narrator. In the “Morning Songs”, the author is at home and at ease. The poems in this part convey a sense of hope and warmth; they are bursting with life as they follow the activities of several mornings. Just as the morning marks the beginning of the day, the poems within this part prepare us for the challenges of time. The “Afternoon Songs” deal more closely with the passage of time. The narrator undergoes or begins to expect a transformation into adulthood. At this stage, the author has not yet left the realm of childhood but begins to slowly make her departure. Her departure is marked by a gradual exit out of the natural world; the conversations she held with birds in the first section are now replaced with doubt about the birds’ ability to communicate. Finally, in the last section of the collection, “Evening Songs”, the narrator is in an unfamiliar place searching for traces of home in the mundane and routine parts of life. Assumi’s desire for these poems is to renew a tradition and to award the mundane with the attention it no longer receives. In honouring the legacy left behind to her, she imparts wisdom upon the rest of the world. In her poems about the multiple parts of a singular day, she takes the readers through a journey- life begins with the sun, but it continues even in darkness. Assumi guides the reader to a truth that the world overlooks: there are lessons to be learned in the ordinary.