Published by Penguin Random House India 2025

Review by Kevileno Sakhrie

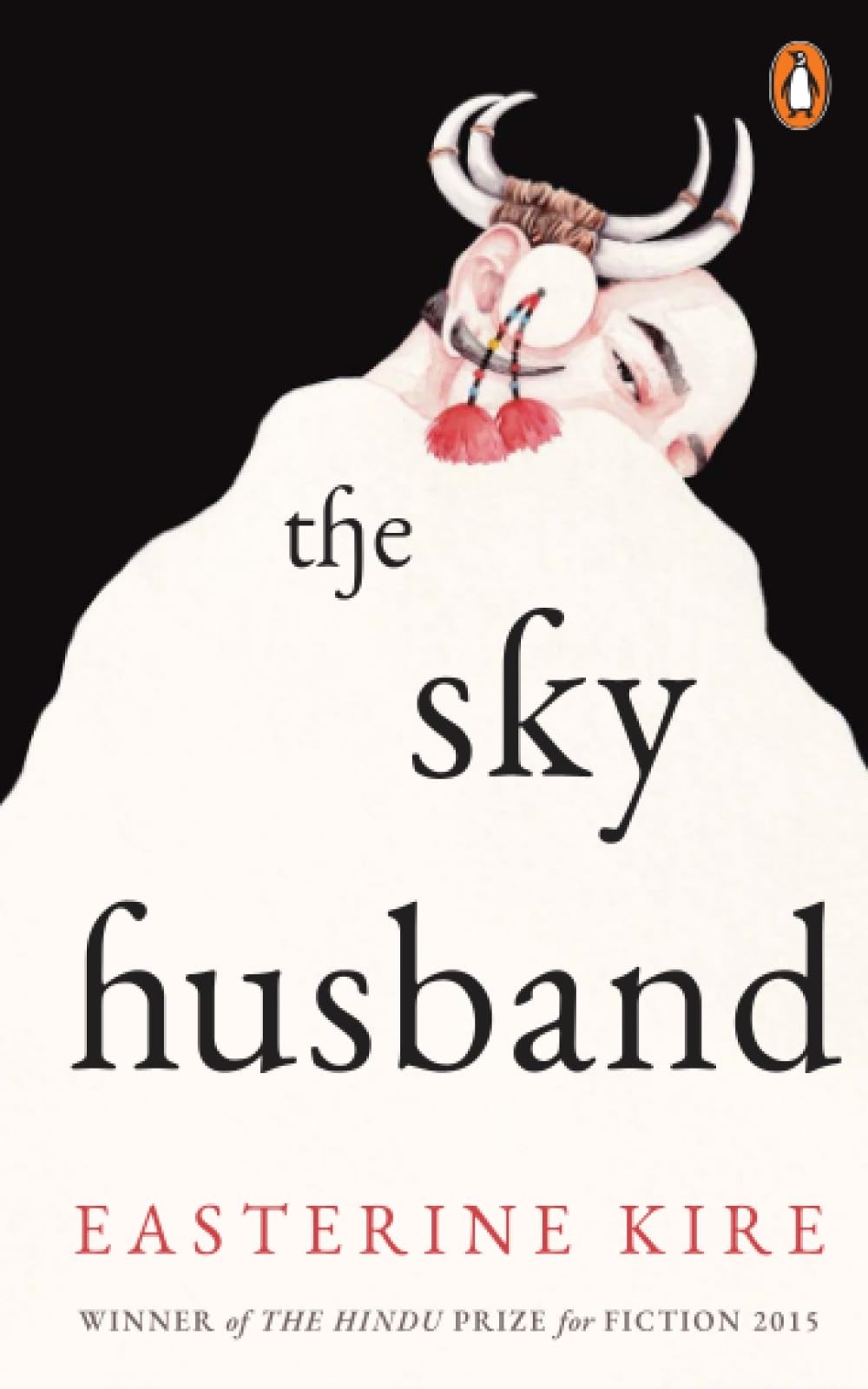

Easterine Kire’s latest offering The Sky Husband is a luminous collection of short stories that brings the living legends and stories from Northeast India into sharp, contemporary focus. This book had me by its cover- a more mesmerising and breathtakingly beautiful cover I cannot imagine. Nor did the book disappoint: it was as intriguing as its cover. The Sky Husband bears all the hallmarks of Easterine Kire’s narrative powers: her linguistic dexterity; her genre bending; her virtuosic gift for interweaving stories on multiple levels, from the literal to the metaphoric, the folkloric and the mythic.

Drawing on both lived experience and cultural memory, Kire brings together eight powerful original short stories that are studies on love— the lores of affection, the psychological need to love and be loved as also an examination of the throes of separation, whether by circumstances beyond one’s control or by death. The stories feature characters who grapple with different aspects of love—from desire, passion, enchantment, affection to yearning, endearment and most of all that indelible, overwhelming first love that marks us forever. The collection also operates poetically, riffing on themes that recur like leitmotifs in a musical composition. And as its title suggests, the sky husband is one of its central motifs.

Each story demonstrates how the act of love is maintained by strategic choices that one makes and adjusts accordingly. In the title story, which is set in the deep time of legend, the protagonist makes the unusual choice to marry a mysterious sky husband - a decision by which she stands, come what may. Chan and the Blue Forest explores the aftermath of a man’s encounter with a mystical forest spirit and the impact his decision to go back to his spirit bride has on the characters involved. The Tracker examines the relationship between a husband and wife contextualised by the memory of their shared history as revolutionaries, ultimately finding solace and renewed affection in a shining moment of reconnection. Cherry in Blossoms in April, a personal favourite, tells a poignant tale of wartime love transforming historical document into community legend— a weaving together of historical experience with personal narrative. Sometimes Life is a story of thwarted love set against the backdrop of the famous tea gardens of the Northeast and an imaginative delineation of the cultural and social landscape of the tea-garden communities in these historic plantations. The love interests in this story reappear in the next (a completely different story and setting despite having the same title) as Kire experiments with variation story-cycle or narrative echoing where each story becomes a fresh exploration of the characters’ dynamic - a technique reminiscent of musical variations. Dodili Va’anilo, is a love story with a difference and as I see it, also features a spiritual sky husband. The last piece in the collection highlights the mutual appreciation of two soul mates and the deep and sincere embrace which marks the quality of their existence- something that even death cannot diminish.

What makes these stories different is that they transcend conventional romance plots by intertwining love with themes of cultural identity, survival, and the profound connection to land and community. Instead of isolated affairs, the nature of love as depicted by Kire in these stories is shown as acts of resistance and continuity, ones that affirm indigenous relationships and assert indigenous ways of knowing.

The stories demonstrate several key aspects and elements of indigenous cultural heritage. Firstly, they draw from oral history the techniques to perfectly capture the character and texture of life in these regions. The title story, for instance, is found within the fabric of north-eastern folklore and provides the theoretical framework for Kire’s story. However, while the author is drawn to this folktale about a young girl who prepares to marry a “sky husband”—a man she has never met except in her dreams— as a creative storyteller, she takes the seed of the tale and turns it around to fit her own telling. Aniya, the girl protagonist of the story, inexplicably feels a profound love for a person she knows only in her dreams and despite her mother’s misgivings is committed to this mysterious being. Her apparent contrariness does not come from pride or disobedience but from a different source. She chooses her husband according to another set of values than that of her parents, motivated by a higher moral order than those around her. Her self awareness and stability of mind leads her to explore dimensions not clouded by disturbance and dopamine culture. She seeks more than what the surface can offer. It isolates her and sets her apart, but she accepts that it is her path, her destiny. And that is why she is the stuff out of which indigenous legends are born.

The supernatural occurrences in some of the stories attest to the alternative reality often presented in Kire’s cultural discourse. It is indicative of the cosmology, the way in which indigenous people looked at the world. This has always had a very strong place in her work. The acceptance of the supernatural is blended simultaneously with a profound rootedness in the real world with neither taking precedence over the other. It paves the way for some great examples of genre bending in Kire’s work. Another tangible element of indigenous storytelling is the relationship between land and narrative. This author firmly believes that certain indigenous stories should be understood as inseparable from particular locations in the writer’s or teller’s traditional territory. The unity of story and place in these works is a powerful source of indigenous sovereignty, and an assertion that this land is full of indigenous lives and stories. The reference to specific places in the stories are not simply local colour or embellishments added by the storyteller. They are often a crucial part of the lessons embedded in the narratives, because these stories are also about how to survive on the land. They prove how the stories have grown out of a profound and long-term relationship between the land and the people. The geography and topography serve as mnemonic devices in such stories. A case in point is Chan’s Blue Forest. When people see this place or hear of it they remember the stories associated with it and often re-tell the stories to others. It thus functions as a site of profound storytelling.

Kire writes tales that can be told or even recited to an audience. Envisioned by her, the short story is seen as an evolution of the tale- a partnership of two forms, oral and written. She knows that a writer doesn’t always have to write for readers, but can write for listeners too. Hence, the extensive use of dialogue, poetic language and snippets of song in these stories. Further, her participatory endings are reflective of indigenous storytelling traditions where endings are often unresolved inviting debate and discussion among the listeners/ readers. Her stories have gaps and spaces so that the reader can come into it to make the story, to feel the experience. This is demonstrated to great effect in the powerful climax of the titular tale, with the community or the reader at large commenting on the action long after it has ended. At the same time, the participatory ending compels us to focus on another conflict- the dominant western notion that science is the sole explanation of the universe. The ending is unresolved but the question remains: which perception of reality are we to believe? There is both a question and a caveat for the reader in this.

The Sky Husband is an unforgettable journey through myth, memory, and modern identity. It has Easterine Kire telling her stories her way, showing us the beauty, the pain, the joy, the romance — and the pride of where she’s from, who her characters are and what they’re aching for. Compelling and memorable, this is a major new work by the Sahitya Akademi winning novelist, writing at the top of her game.