'I find solace in songs': An Indian garment worker on life under lockdown

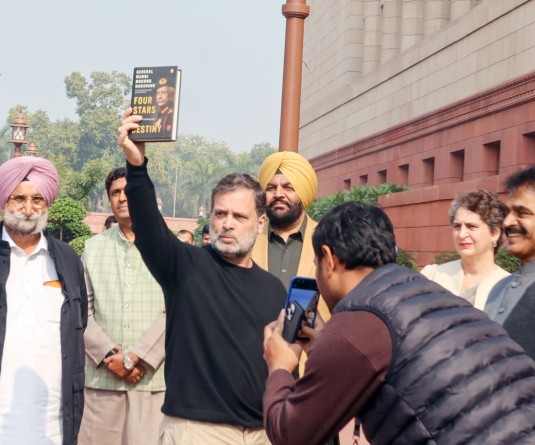

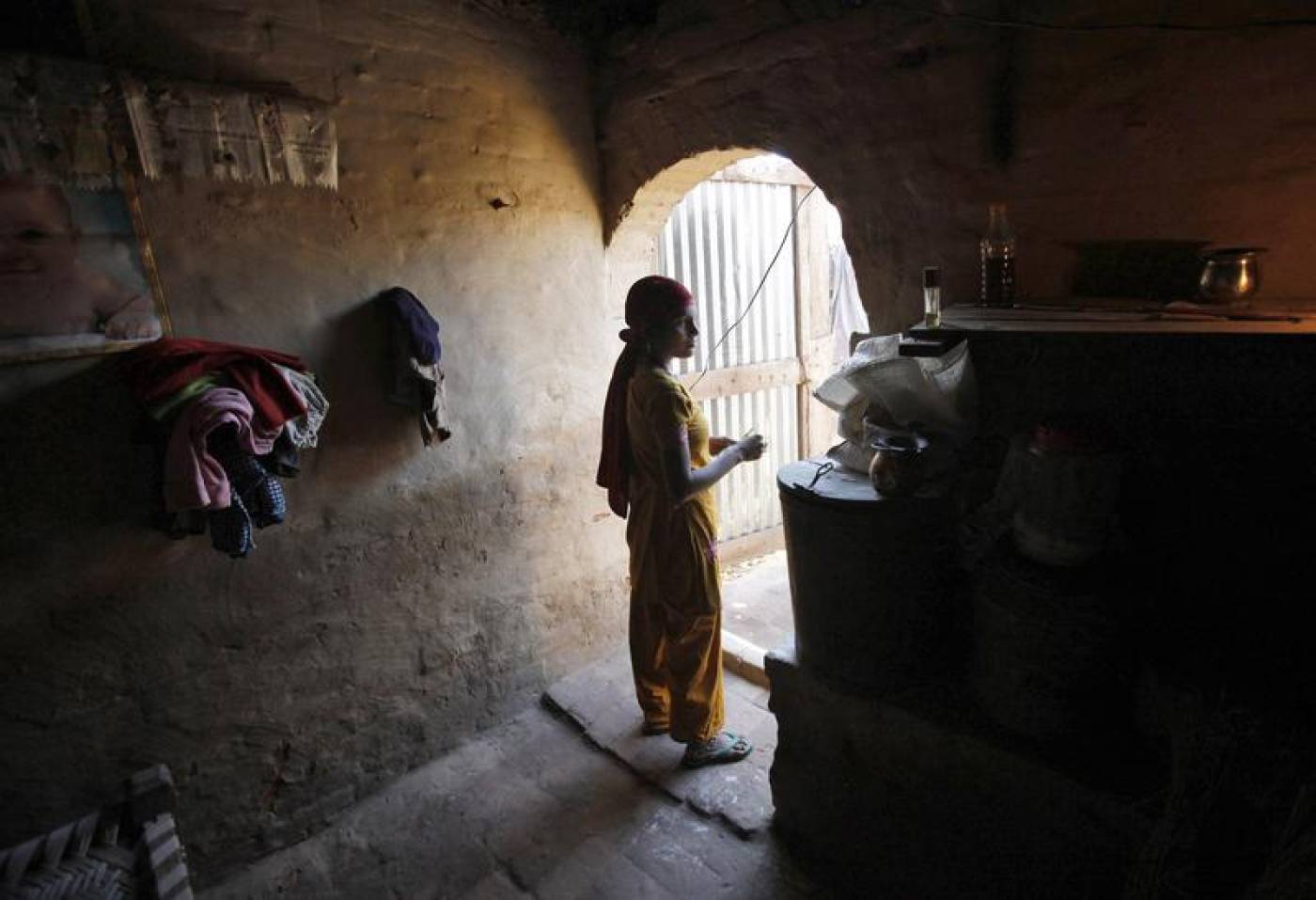

A woman labourer watches television inside her house at the compound of a factory at Libbar Hari in the northern Indian state of Uttarakhand January 23, 2011. REUTERS/Adnan Abidi

"I don't know if I want to stay and work here. I will wait for the lockdown to finally end and then decide. Till then, I have my songs."

CHENNAI, April 22(Thomson Reuters Foundation) - When she waved goodbye to her village and her parents eight months ago, it was exciting to imagine life in a faraway city and a job as a tailor in a factory.

But for one 18-year-old Indian garment worker, who fast became disheartened by the arduous shifts and harsh factory conditions, the coronavirus lockdown has made her long for her distant home, and worry about what the future holds.

As the government keeps factories closed to fight the spread of the virus and global fashion brands cancel orders, millions of workers in India's textiles and apparel industry - most of them women - are in limbo and fear they could lose their jobs.

Tens of thousands of them, including the 18-year-old tailor, are stranded in cramped accommodation on factory premises where social distancing is almost impossible.

More than 1,000 km (600 miles) from her village in a staff hostel in the southern city of Bengaluru, she said she feared being reprimanded for speaking to anyone other than a family member and asked to remain anonymous.

This is her story:

"My home is near the forest in Sundergarh in Odisha and it took me one full day on the train to get to Bengaluru. I was excited that I was going to work in a big city but even after so many months, I don't know what Bengaluru looks like.

From the station we were brought straight to the factory hostel, and then the routine set in. I would go for my shift to the factory and come back to my hostel room when it ended.

Once a week, I would be allowed to walk a little further down my street to buy a few essentials and then back to the room-to-factory routine.

So I don't know what the city I migrated to work in looks like. Now I even miss the five-minute walk from the room to the factory and back. That would be freedom now, considering that I can rarely leave my room.

There are four floors in this hostel building and I share my room and toilet with nine girls. We're given mats to sleep on the floor and have access to a kitchen, where we can cook small meals.

Today I ate rice and potato curry. That's all we had to share today. It is difficult to get permission to go out to buy things. There are always so many restrictions, because there are rumours that many people have corona fever in this area.

Different coordinators keep giving us instructions about safety. First we were told to drink hot water, wash our hands and be hygienic to protect ourselves from corona fever.

A few days back we were told to save whatever money we have in our accounts because there's no guarantee of orders coming or us resuming work soon.

Everything's very unsettling and there's nothing to do all day, except lie down, cook, eat and worry. There's no TV, no games and nothing to do. I miss my village and its openness. Now I think everything is so much better in the village.

I speak to my parents every day, sometimes twice. They're also in lockdown but for them the restrictions are not so strict. There is the forest nearby and they have each other too.

All I have are songs on my phone. I keep listening to them, humming along and it makes me happy. I find solace in these songs.

I also spend time thinking about how I was trained to be a tailor but that's not exactly the job I have in the factory. Instead, I have to trim extra thread or turn stitched clothes inside out.

I was trained for two months back home and then sent to this factory with a few other girls. We work on mostly boys' clothes and sometimes dresses. I think they're sent out of the country, but I don't know where.

I hear that the clothes we stitch are very much in demand and fashionable. That also makes me happy, like the songs.

When I was working in the factory, there was no time to think about home or family. The shifts were long and so many of my friends kept complaining of aches and pains. They kept popping pills to be able to continue work.

I'm stronger and don't have those aches and pains. So I work hard because the 8,000 rupees ($105) I earn is important for my family back home.

But these last two weeks, I've been really missing home. My mother also keeps telling me to come back. She says we'll manage because we'll be together.

I would have argued with her and said the money was decent. But now, I don't know if I want to stay and work here. I will wait for the lockdown to finally end and then decide.

Till then, I have my songs."