BY SAEED NAQVI

IANS | October 5

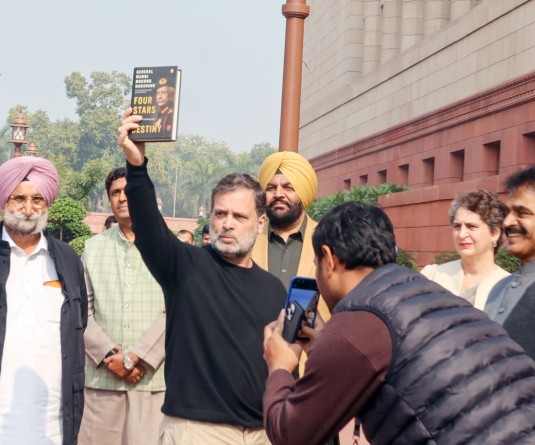

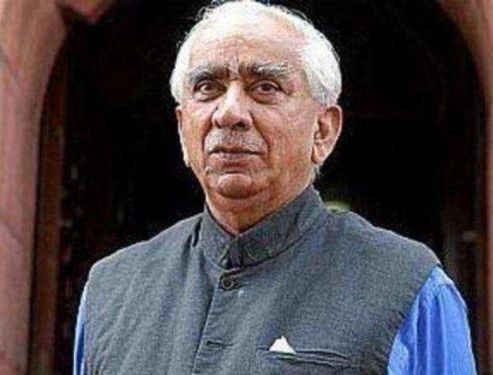

Jaswant Singh's final goodbye acquired extra poignancy. Ushered into his study in my mind's eye by the reliable Thomas, his secretary, I can see him induce a smile by way of politeness, gesture with his right hand, slowly nodding his head disapprovingly. He would have been pained at the Hathras rape and a blanket "not guilty" verdict on all and sundry accused in the Babri Masjid demolition conspiracy case. He was a gentleman politician with whom one could disagree and yet return satisfied with many takeaways. He had the rare ability to change his views (as on Jinnah) if that is what the evidence suggests.

Jaswant Singh reminded me of Ismat Chugtai's description of Dilip Kumar who acted in films for which she had written the script and which her husband, Shahid Lateef, had directed. "Dilip Kumar is not a handsome man but he knows how to act as one."

Likewise, Jaswant Singh's "haw, haw" English was plausible, if not always authentic. He spoke with deliberation which was custom made for pauses enabling him to pluck out words he enjoyed using. His feudal Rajput background, polished by his years at the National Defence Academy under the supervision of Commandant Leslie Keith Malcolm (Bonny), a fastidious Scottish officer, his yen for polo and custom made safari suits with epaulettes (sans insignia), all these enhanced his aristocratic bearing.

The 'style' came in handy when as External Affairs Minister, he kept Bill Clinton's Deputy Secretary of State, Strobe Talbott, in his thrall during the marathon series of exchanges on the nuclear issue.

In the choreography of Atal Behari Vajpayee's cabinet, the Jaswant Singh persona had a deliberate placement. Was his 'princeliness' a criteria? That would have exposed Vajpayee to the charge of having a class fetish. After all, the Minister of State in the foreign office, Vasundhara Raje was a thoroughbred princess. It was Vajpayee's larger than life figure, his seniority over any RSS chief during his time, his evolution into international cosmopolitans through the Nehru years, his incomparable oratory and a natural bent for deep reflection, left in him no smallness of mind to nurse prejudices or be overawed by 'style'.

Jaswant Singh's flair was allowed full play in the cabinet but the reins were firmly with Vajpayee, something which became so clear when Vajpayee flinched away from what would have been a disastrous military engagement in northern Iraq and on which Jaswant Singh had set his heart. Having pulverized Iraq in April 2003, the US thought of sharing administrative responsibility with 'allies' on what it imagined was a 'conquered' oil rich country. Blandishments came India's way.

Singh was not the only one so dazzled by the projection of American power on new global television, particularly the hyped up drama on April 9 on the pulling down of Saddam Hussain's statue: the story put out by the US was that the statue had been pulled down by anti Saddam masses. Nothing of the sort had happened. That's another story which must be told in detail.

The pulling down of the statue registered with Vajpayee as the rise of an "awesome power", an event which dictated that festering regional conflicts should be ended. A week later, on April 18, 2003, while on a visit to Srinagar, he held out his hand of friendship to Pakistan. This, despite the two armies poised for military action -- after Operation Parakram. Jaswant Singh saw the same events somewhat differently: as a confirmation of a powerful unipolar world. India had come so close to this powerful entity that a bonding was full of promise. Hence his enthusiasm for an Indian role in Iraq. India was to take charge of the Kurdish North -- an imperial role at last. Something in Jaswant Singh was turned on.

A senior Indian diplomat was dispatched on a secret mission to gauge the level of hospitality India would receive, should it accept its new imperial role. The diplomat returned after meeting Masoud Barzani, Jalal Talebani and, by way of a bonus, with a bag full of truffles strewn all over Talebani's Estate.

With foresight, the diplomat made a clever detour to Dubai to establish contact with Adnan Pachachi, a former Iraqi Foreign Minister who the diplomatic grapevine in West Asia tipped as the possible front for the new 'conquerors' of Iraq.

The Indian Ambassador to Iraq, B.B. Tyagi, had been parked in a three star hotel in Amman, waiting for the Americans to declare themselves the country's new rulers. Tyagi would charge down and present his credentials. Such unseemly obsequiousness.

Away from the herd, Vajpayee had made his own calculations. He realized his cabinet colleagues had been taken in by the sole superpower moment. At this moment (his colleagues thought) it would be tactless to refuse an American invitation. But Vajpayee asked tough questions. A Division plus 8,000 soldiers and men would be required. The thrill and grandeur of the expedition was alluring, but not if New Delhi had to foot the bill. Permanent membership of the Security Council would be worth the gamble but that is not what the Americans were talking about.

Vajpayee the skilful politician came into play when he called up CPI leader, A.B. Bardhan, a friend of many years. Would Bardhan be happy at the sight of Indian troops, in Division strength, operating under US command without a UN flag? Vajpayee's signal to Bardhan was to mobilize public opinion against the idea. Not only would it help India, but it would enable his colleagues to slide down the pole they had climbed up to impress the Americans.

That Singh corroborated to me bits of this untold story, a story in which he himself does not come out smelling of roses, shows the kind of gentleman he was. In fact Vajpayee's was a cabinet of women and gentlemen, a few rotten apples notwithstanding. Supposing Prime Minister Narendra Modi stood in front of a mirror and kept a photo of this team of seniors by his side, for easy contemplation, I wonder what thoughts would cross his mind.