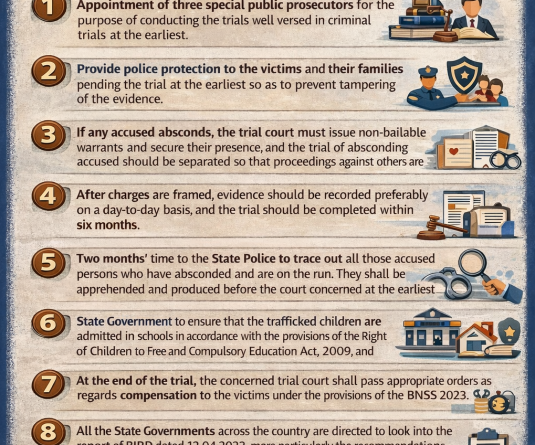

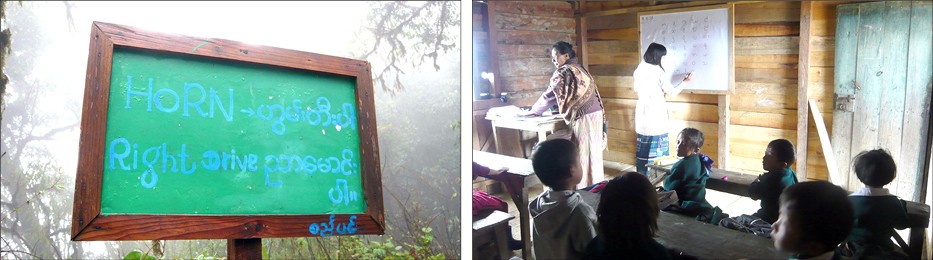

(Left) A simple board marks the border between Tusom and Somra or India and Burma. (Right) Class IB of Tusom (CV) Primary School is taught Burmese letters, as an initiative to communicate better with the people of Somra in Burma. (Morung Photos)

Whatever can be conceived is possible and whatever is possible can be conceived

Morung Express Feature

Ukhrul/Somra | May 19

Imagination is a multi-edged tool. It can be deployed to fashion solutions that currently seem out of rational control. It can support the yarn to weave a guide to possibility. And now, as ever, is a time to apply imagination to the Naga reality to obtain desired futures. Thus, set out a team of imaginative Naga people to reach out to those who are considered part of a shared future but often forgotten—pushing one boundary, emerging on the other side of another; from India, a stone’s throw away into Burma.

Somra is the first Tangkhul Naga village in Burma after Tusom, the last Tangkhul Naga village in India. And while travelling between the two, it is hard to tell when the international border passes you by. A small green board with blue lettering marks the border—you can make out what it says completely only if you read Burmese, the English words on it being ‘horn’, ‘right’ and ‘drive’. A big tree fallen over the road, as a single line canopy, a few meters into Burma is a more dramatic marker of this “imagined boundary” that separates more than 300 Tangkhul Naga villages into India and Burma. 33 of these are in Burma.

To tie up loose ends between these villages, a troupe of film-maker, writer, activists, anthropologist, conservationist and musicians reached out to Somra in the first week of May to celebrate Somra’s seed-sowing festival, He Khreng Bou Twei. The festival is celebrated in all the 33 Tangkhul villages in Burma, marked by traditional music, feasting, games, a modern guitar-wielding here, fashion show there.

Trade and cultural exchange between the two sides have fostered to the extent possible over the years. That said, making available in Somra Tract what is available in Ukhrul District is no mean feat. People from the Somra Tangkhul Hills walk hours through thick forestation, now marked by a single road, to facilitate this availability—the road a product of individual efforts, not of the nation states that engulf its two sides. The resultant trade is hardly enough for the Tangkhul people in Burma to afford identity markers such as hand woven shawls and skirts, and the luxury to identify with the Nagas in India keeps a watch from afar. But kinship and clan legacies provide for the strong pull that economics and established politics do not yet.

With the two nation states bent on making peace through armed violence, initiating dialogue between people as a way towards peace, re-connecting and re-strengthening relations can be physically and figuratively arduous.

Somra village is approximately 150 Km from Manipur’s Ukhrul district headquarters. To reach Somra, one has to take a circuitous broken route unknown to Google Maps, taking a detour to Tusom from the junction that bifurcates also towards Jessami, heading to Nagaland. Most of the roads on the Indian side of the border are the standard North East roads—they exist but in their rugged fresh cut black-topped-once form. The Challou River flows on the way to Tusom, with no bridge over it to date. If it rains, the river gets too big to cross for cars going to or coming from Tusom.

Now, Tusom is a trifurcated village—old, new and Christian Village (CV). The people of the Tusom villages have not only interacted most with the people of Somra, but also shared similar experiences, both being peripheral to the centrality of the nation state each now “belongs” to.

At the time when Yangon was not as accessible to the Naga people in Somra Tract, they have studied in the same schools in Ukhrul, read the bible in the same language and had similar cultural experiences.

They faced similar army abuse—if Burmese junta exploitation was not bad enough, people of Somra coming to trade were subject to abuse by the Indian army too. Shared silence cropped from this. Through them had come efforts that not only resulted in “disciplinary action” against a turbulent army officer, but the eviction of the Gorkha Regiment from the Kharasom/Tusom region in Manipur.

The team going to Somra took the initiative to harness these shared experiences and broaden them, and discovered creativity at its heart. Among others, the Principal of Tusom (CV) Primary School has come up with the ingenious idea to introduce Burmese language classes in the school—to exchange goods and ideas, a shared language or two. A teacher from Somra, her face smeared in sandalwood paste, a popular sunscreen in Somra, imparts basics of Burmese to the students of class I to VI. Instead of the east always at the mercy of the west, the tables turn to advantage the east, engage with it.

As the team headed east, from Tusom, the route became even more encouraging; roads made known their object as more than colonial enterprise. The road between Tusom and Somra was constructed only by 2007. Neither India nor Burma spent any effort on it. It is the child of community enterprise, efforts pooled in by Naga individuals who refused to succumb to alien boundaries. It is treacherous for cars but vastly superior in its intent and purpose to similar broken ignored roads that are a product of state enterprise, both in Nagaland and Manipur. The journey of around 16 Km, from Tusom to Somra, takes around two hours to traverse. The stuntman gearless Burmese bike, Sikay, can cover this in about an hour.

Somra comes suddenly out of this road, at the end of it, in Burma. Declared a sub-township in 2009, Somra is a part of Leyshi Township at the moment, which is a subset of the Naga Self Administered Zone. It is a quiet little village of 500 households with tinned roofs—all the villages in the surrounding hills could be spotted by their CGI-sheet rooftops, the sheets manually brought from Ukhrul.

…to be continued