Fig. 1: a. Elder man adorned in past Konyak traditional hairstyle; b. Elder woman from the Ahng (royal) clan; c. The last tattooed man; d. Na-gha (ear-piercing) practice of Konyak. Source: Fieldwork in Chi Village, Mon district, Nagaland, India; 2019. Photographer: Amo Konyak B

Dr Amo Konyak B

I grew up hearing stories of my ancestral belongings being burned down, but conducting my doctoral fieldwork made the weight of these stories much heavier. What disturbed me even more was the realisation that, while original artefacts were destroyed in our villages, many survived elsewhere. I was aware that some Konyak belongings and artefacts were preserved at the Pitt Rivers Museum in London. But during a repatriation-related dialogue in 2023, I learned the sheer number of objects housed there. This stunned me. In our villages, children grow up seeing only replicas, while the originals, the ones made, worn, and touched by our ancestors, remain locked away in distant museums. This is the reality. It is ironic and painful. What was burned here in the name of faith and religion in the Konyak villages was being protected in museums like the PRM in the name of knowledge.

As a Konyak Naga researcher, another revelation shook me even more deeply. The discovery that not only material artefacts but also human remains of my people were kept in museums such as the Pitt Rivers Museum and other institutions across Europe. Until then, I had only known about material artefacts. To know that the remains of our ancestors had been taken far away filled me with shock and grief. According to Konyak belief, every person must be laid to rest in their birthplace so that the soul may find peace and join the ancestors in lünbüh chang- the village of souls. To learn that some of our people were denied this final return was deeply unsettling. It transformed my understanding of heritage loss from something cultural into something profoundly spiritual.

Understanding the Past

I am a Konyak anthropologist. I began my fieldwork in the Konyak areas as someone returning home, yet also as someone learning to see my own culture for the first time through a different lens. I travelled from village to village across Mon district, north to south, east to west, walking through landscapes that were deeply familiar to me. The people, the hills, the language, and the everyday rhythms were my own. I had grown up within this culture; my identity as a Konyak was already written into me at birth. I believed I knew my culture because I had lived it. Yet, as I sat with elders and listened to their stories, I realised that what I knew was only what remained after an enormous erasure.

As I walked through the memory landscapes of my elders, the last tattooed men and women of the Konyak tribe, and those in their seventies who had narrowly escaped tattooing, I encountered a world that I had known only through childhood stories. Almost every narration began with the same words: “Miyang thiyang tüh…(in the past…).” As a child, that past felt distant, almost mythical.

During fieldwork, I understood that this “past” was not even a hundred years away. These elders had lived through the transformation themselves, when men wore the mei (loincloth), and women wore short wrap-around adorned with precious heirloom ornaments passed down through generations; when people walked barefoot on harsh terrain, their feet flattened and hardened by years of labour; when families gathered in longhouses around the central fireplace before electricity arrived. To walk barefoot, once a sign of endurance and strength, is today seen as a marker of poverty.

As their memories unfolded, I began to see clearly how radically the coming of Christianity reshaped the world they once knew. The elders spoke of life before Christianity and life after Christianity as two entirely different worlds. Warfare stopped, open burials replaced by cremation, and the Konyak funerary effigy replaced by the Christian burial stone marked with a cross. There were other changes too. The morung, once restricted to men, was opened to women, and tattooing on the face, chest, shoulders, hands, and legs, once regarded as symbols of bravery for men and beauty for women, was abandoned. Rice beer, once brewed in every household and believed to restore strength after hard labour in the fields, was prohibited, leading to the disappearance of the practice. Ear-piercing (na-gha) adorned with deer horns, porcupine spikes, and coiled brass also vanished. The blackening of teeth as beautification ended. Even the frontal bob-fringe Manchu queue hairstyle worn by men was no longer practiced. One by one, visible markers of Konyak identity fell silent.

Christianity and Cultural Erasure

I was raised in a Konyak Christian family. My grandparents were first-generation converts, my parents second-generation, and I am a third-generation Konyak Baptist Christian. Today, I feel conflicted. One part of me understands and even appreciates some of the changes. But another part of me feels an unbearable sadness at the scale of cultural loss the Konyak people have experienced. During my doctoral fieldwork, I had to grapple with a difficult question. If so much of our culture has disappeared, what truly remains of our identity? This question became most painful when I interviewed a tattooed elder from my Tamkoang village. One epi (grandmother) said to me:

“Yaosaii saii, tu büh tüh chung yeang üng bu. Hashih tohey üng yam tao thiji khen tük büh tüh.”

“I am ashamed of my tattoo. Why are you writing about it? We were told that tattooing was the worship of devils and spirits, and so it was eradicated.”

Her words struck me deeply. What was once worn with pride has become a source of shame. I realised that cultural erasure is not about destroying material belongings and artefacts. These violent actions also reshape how community members feel about their own bodies and histories.

As a Konyak researcher, almost every interview has a sentence which went like this:

“All our artefacts were burned.”

It was uttered quietly, without drama, yet it carried immeasurable grief. Elders narrated how, with the advent of Christianity and especially during the revival movements across Nagaland, Konyak villagers were instructed to burn everything associated with the old religion. Missionaries and mangtang (spiritual persons believed to communicate directly with God) visited households and ordered families to bring out their ornaments, ritual objects, attire, and household items. They prophesied misfortune if people disobeyed the command to destroy these items. Out of fear and belief in bad omens, people complied. What had been accumulated and treasured as tradition over centuries was destroyed within days.

Findings from my doctoral fieldwork among the Konyak villages in both northern and southern regions of Mon district suggest that, according to oral traditions, the history and origin of many traditional Konyak ornaments and attire extend back several centuries. Konyak Informants believed that their ancestors migrated to present-day settlements wearing the same ornaments. With the advent of Christianity, much of this heritage was reduced to ash in a single generation.

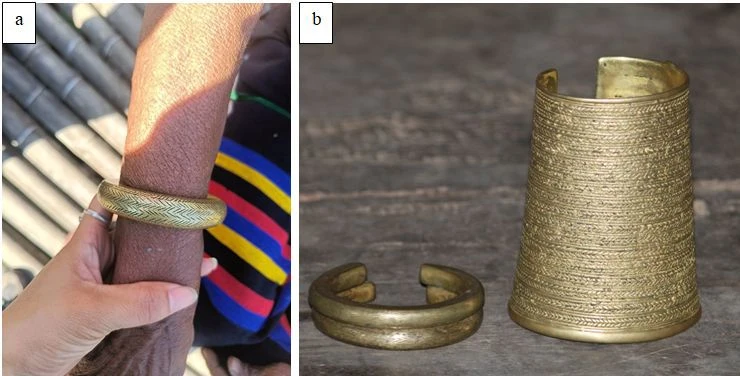

One of the most painful moments of my doctoral fieldwork was when my maternal grandmother from Changlangshu village took out a brass bangle she had secretly preserved. She slowly unwrapped the bangle from an old piece of cloth kept inside a wooden trunk. She told me how she once had many brass hand ornaments. They rang together when she pounded rice. When Christianity came to her village, all her ornaments were ordered by the believers (outsiders who brought Christianity and Konyak Nagas who converted to Christianity) to be burned. Many were also sold to a blacksmith to be melted into gun parts. She kept only one piece with her. She said:

“My eldest son told me that I should at least leave one brass hand ornament for him”

The brass bangle in her wooden trunk is a reminder of a heavy past. It carries the weight of everything that was lost.

Today, in my ancestral village, Tamkoang, there is only one original ancestral brass cuff left. The owner, Mrs Neangmai, told me that her grandmother hid it while burning the rest of her ornaments. Today, during village festivals, the youth borrow this single cuff to represent their heritage. What was once common is now rare. What was once lived is now symbolic.

In Chohzu village, key informants narrated how ornaments, attires, gongs, and even bamboo baskets were burned continuously for two months, as ordered by the church members. One elderly woman from Tamkoang village told me how, as a young girl, she secretly rescued a few ornaments from the flames without her parents’ knowledge. These hidden remnants now survive as fragile witnesses of resistance.

Undoing Conditioned Colonisation

As a Konyak anthropologist, I realise that our material culture today exists only in fragments: as replicas in villages, as memories in the bodies and voices of elders, and as original objects stored in distant museums. The meanings and stories once embedded in these artefacts are slowly fading with each passing generation. Much of what we now know survives only through oral narratives told by elders in their seventies and eighties. With their passing, an entire archive risks vanishing forever.

Artefacts are not merely objects of the past. They are our belongings and are carriers of memory, skill, belief, identity, and history. When artefacts are burned, as I recorded in my doctoral work and documentation project, it is not only the tangible heritage that disappears, but also the intangible heritage; the memory of a people is lost. When artefacts are removed to distant museums, they survive physically but are severed from the communities that once gave them meaning. Today, the Konyak stand at a fragile cusp of history. The last living witnesses, as our elders still remember what once existed, yet most of the cultures have already vanished from the land. This is precisely why documenting Indigenous artefacts as heritage in Naga society is no longer optional. Communities like the Konyak Naga people, this is even more urgent. To document what survives in memory, in museums, and in the few remaining heirlooms is to acknowledge that we (as Nagas) must examine how our minds and practices are conditioned by colonisation. We must be accountable to one another and ourselves for the violence we have inflicted on ourselves in the name of faith and progress. For me, this path is not an academic exercise. It is a collective moral responsibility to ensure that what was burned, taken, and almost forgotten is not erased from our history.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Professor Dolly Kikon, Professor of Anthropology and Director of the Centre for South Asian Studies (CSAS) at the Humanities Institute, University of California, Santa Cruz, for her encouragement and guidance, which inspired me to write this reflection. I am deeply thankful to the Konyak key informants and elders who generously shared their memories, experiences, and past traumas openly and with trust during my fieldwork. Their willingness to revisit complex histories made this work possible. I remain grateful for their courage, hospitality, and wisdom.

[Note: It is important to clarify that this reflection does not seek to assign blame to any individual, organisation or belief system. Rather, it documents a historical period of profound socio-religious transformation in which religious change, colonial encounters, and local social dynamics together reshaped Konyak culture and the people. The intention is not to accuse, but to underline the loss of both tangible and intangible heritage that occurred during this transition, and to emphasise the urgent need for documentation and preservation at this critical moment.]

Dr Amo is a Konyak Anthropologist. She obtained her PhD in Social and Cultural Anthropology from North Eastern Hill University, Shillong, Meghalaya and is currently an independent researcher. This reflection is drawn from the author’s fieldwork conducted for her PhD thesis titled “Marriage among the Konyak Naga of Nagaland” and documentation project for a book titled “Konyak Pulang Ow Hei Leng (Konyak Naga Traditional Attire and Ornaments).” The author can be reached at: [monyubelle@gmail.com]