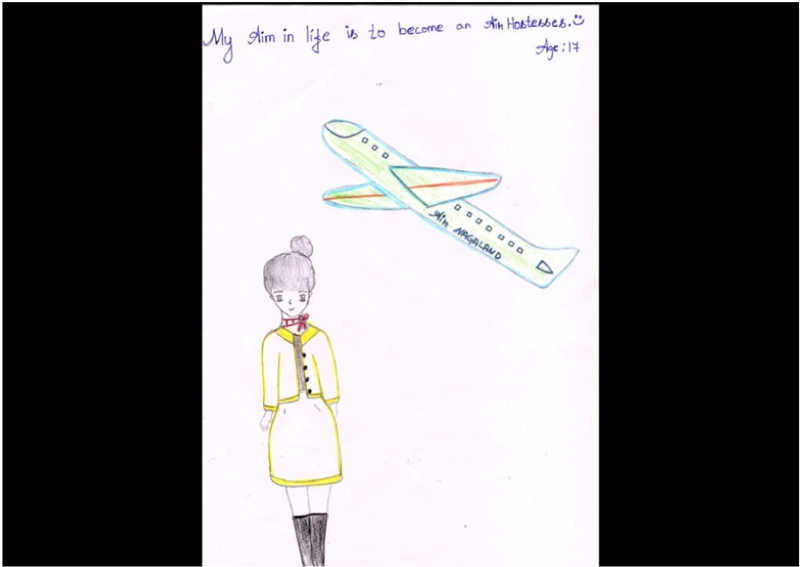

Image 1. Photo by Longshibeni Kikon

Review by: Elspeth Iralu, University of New Mexico

How are children experiencing the pandemic? How does the pandemic exacerbate the challenges vulnerable children face? What dreams sustain children?

During the Pandemic, an online art exhibition by children from violent homes in Nagaland (northeast India) offers a path through which to consider these questions. The exhibit is made up of over 50 original drawings by children, photographs of the process of creating the drawings, and several videos in which the artists share their work and describe how the drawings illustrate their lives during the pandemic. Curated by Naga anthropologist Dolly Kikon, the exhibit is a collaboration between Nagaland-based Sisterhood Network, an organization focused on empowering women socially, economically, educationally, spiritually, politically, and legally through livelihood skills training programmes, women’s collectives, women’s entrepreneurship, community development initiatives, campaigns, and legal interventions, and Prodigal’s Home, an organization that started with a focus on HIV/AIDS intervention with women and vulnerable children and now addresses community health, women and child development, and rural development.

The curator’s statement accompanying the exhibit describes the emergence of this exhibit as “part of an ongoing campaign to address gender violence in Nagaland.” The pandemic, Kikon asserts, has only increased reports of domestic violence and poor mental health, risking the lives of women and children in Nagaland.Concerns of containing the virus have led to school closures and loss of work and income, leaving children from violent homes few places for respite. This situation has also overwhelmed frontline social workers in Nagaland, who already bear the brunt of addressing the trauma and challenges of gender violence in a region that continues to experience armed conflict, violence, poverty, and other disparities. Kikon writes: “During the Pandemic stands up with children and women impacted by gender-based violence. It celebrates the lives of vulnerable children, commitment of social workers, care providers, policymakers, practitioners, researchers, and volunteers in Nagaland and beyond.”

Photos by Longshibeni Kikon, Operational Head with Toka MPCS in Dimapur, depict the artists at work, using pencils, crayons, and markers to draw on paper. Some children sit on the ground with a folder or board as drawing surface. Others sit at a table or a crate on the ground as they draw. In one photo, two artists draw simultaneously on the same the paper [Image 1].

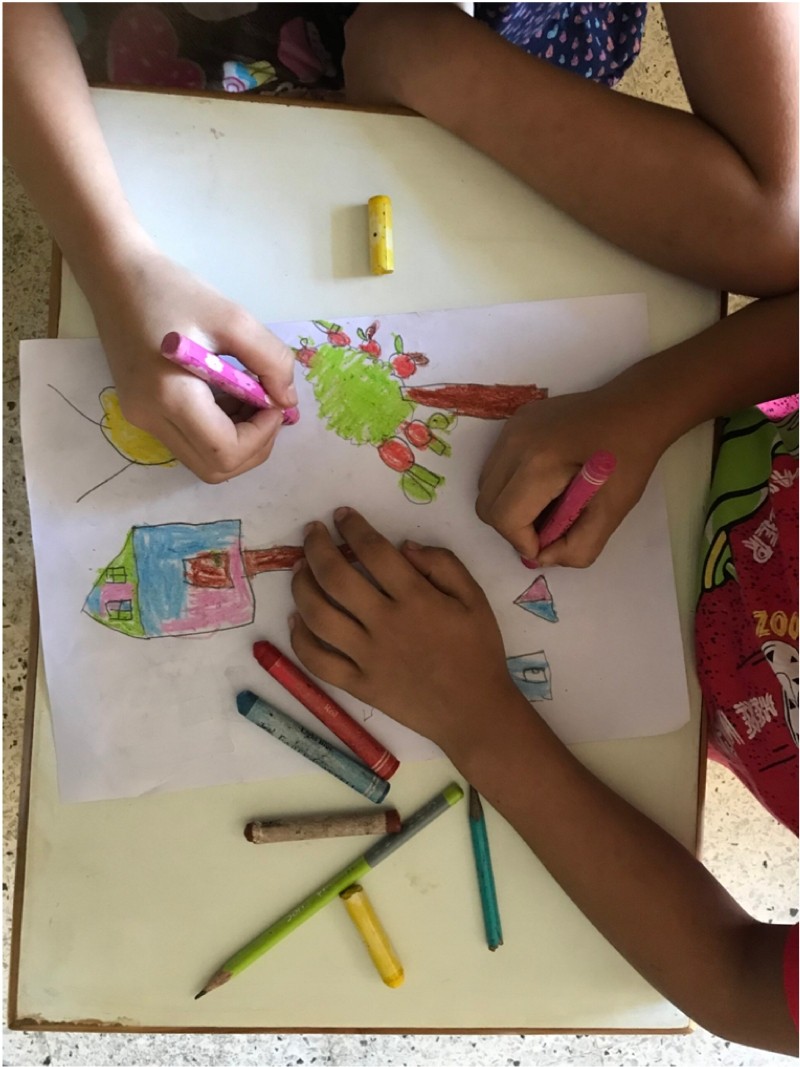

The artists depict their routine lives, juxtaposing happy childhood moments with violent, fearful moments. A series titled “I am a Princess” includes a short video of the artist describing her drawings in succession in conversation with a social worker. In the first image, the artist shows the road between her home and school, in the next, her birthday, then an image of studying and playing, and an image titled “happy family” depicting her parents, siblings and herself. She continues, showing images of watching tv, eating breakfast, lunch, and dinner, then sleeping. “After that,” the artist states in the video, “My father beat to my mother. And in the last, I became a princess! The end.” In the first of these paired images, a stick figure with a zig zag for a mouth, labelled “Father,” holds a stick menacingly at another stick figure labelled “Mother.” Wavy lines representing tears run down from the mother’s eyes. Next to the mother is a frowning face with no body, with the same wavy lines for tears. In text, the author has written: “My father beating to My Mother.” The image is primarily in black and white, the only color on the page the pink of the mother’s skirt and the bright yellow of the crying face with no body [Image 2]. In contrast, the following image “And after that I became a princess” is rich with color. The red-doored pink castle matches the color of the ballgown worn by the artist in this self-portrait. The artist-as-princess stands with her feet in a wide stance, hands assertively placed on her hips, wearing a crown, dangly earrings, and a wide smile. A lush green tree, grass, bright sun, and blue sky filled with flying birds give the drawing a sense of vibrancy and life [Image 3].

Gender-based violence emerges in these images, not as an exception, but as an ordinary aspect of the lives of many women and girls. In one image, an artist depicts herself in a house, being beaten with a stick by a woman. Tears pour down the drawing of the artist and there are two small stick figures, presumably children, watching and smiling. Outside of the house is a paddy field, with smiling people, butterflies, animals, birds, and trees [Image 4]. A caption accompanying the image states: “The artist currently lives in a rehabilitation home and is in second grade. She used to work for a Naga family as a domestic help who regularly abused her. She said, ‘It [the art] is about my past. My parents live in the village and work in a farm. We speak on the phone. I do not know if they will come and meet me.’” Another artist drew an image of herself and her brother, explaining that she left her studies and worked as domestic help in order to earn money to send her brother to school. Multiple images depict boys sleeping, playing, or receiving gifts like ice cream while girls fetch water and firewood or sweep.

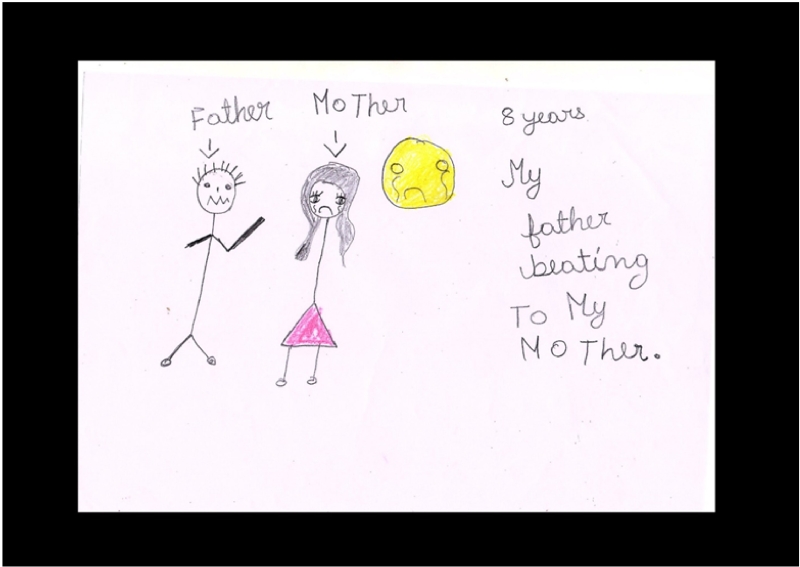

Images of past violence contrast with images of present experiences of the pandemic and hope for the future. In some drawings, artists mourn the losses of the pandemic and illustrate the changes the pandemic has brought, such as not being able to attend school or having to wear masks in public spaces. Images of the future imagine careers, loving families, and a nurturing relationship with the land, such as in images like “My Paddy Field,” which depicts a rice paddy field encircled by mountains and a river inhabited by fish [Image 5].

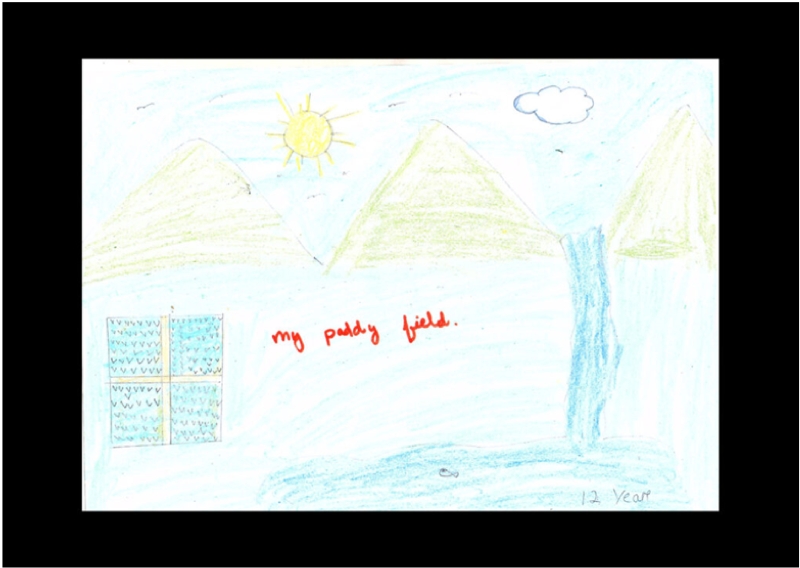

Other images envision a future not just for the artist, but for Nagaland. One drawing by a 17-year-old artist is titled “My Aim in life is to become an Air Hostesses.” This image depicts an air hostess, neatly dressed in a matching yellow jacket and skirt, with a red scarf jauntily tied around her neck, hair neatly pulled into a bun on the top of her head. Behind her, a plane is suspended in lift-off, with the logo “Air Nagaland,” thus far, an imaginary airline. This artist imagines not only what her future could be as an air hostess, but also suggests a vision of what Nagaland’s future might hold [Image 6].

The images in During the Pandemic provide moving insight into the past, present, and futures of Naga children from violent homes. I have spent several hours with these photos, reflecting on the lives of the artists, and considering how this online format allows viewers all over the world to share in their stories. What sticks with me is the artists’ matter-of-fact portrayal of life during the pandemic, refusal to shy away from the truth, and their collective dreams for better futures.

To support the work of Sisterhood Network and Prodigal Home through their rehabilitation and educational programs as well as care and advocacy activities, please consider contributing to these organizations or sharing this art exhibit with your networks.

Azungla James, Director, Sisterhood Network

House #136, Central Apartment,

Near Nagarjan Police Point,

Dimapur – 797112

Nagaland, India

+91-8787501940

+91-3862-224517

sisterhoodnetwork2012@gmail.com

Ela Sani, Director, Prodigal’s Home

NSCB Building, 5th Floor,

Khermahal,

Dimapur – 797112

Nagaland, India

+91-6009015558

+91-3862-233410

prodigalsh@yahoo.co.in

Image 2

Image 3

Image 4

Image 5