Amba Jamir

(Policy Analyst and Development Strategist)

Article 371A stands as one of India’s most distinctive constitutional provisions. Forged in the crucible of Nagaland’s statehood in 1963, it ensures no Central law on Naga customs, religion, or land ownership applies unless the Nagaland Legislative Assembly (NLA) consents. This powerful veto is a shield, safeguarding Naga identity and the sacred bond with ancestral lands, a hard-won legacy of autonomy.

Yet a subtle distinction lurks beneath its strength. Unlike the Sixth Schedule, which empowers tribal councils in other northeastern states with direct authority over land and governance, Article 371A channels power solely through the NLA. It offers a defensive veto, not a proactive guarantee. The shield repels external laws, but without robust state legislation, this protection remains brittle, especially as mounting pressures on Naga autonomy expose gaps in legal safeguards.

The Constitutional Trap

Nagaland wielded Article 371A to veto the Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980 (FCA), shielding community forests from Central interference, a stance reaffirmed by the NLA’s 2023 resolution rejecting the FCA’s 2023 amendments. Yet this victory birthed a legislative vacuum. The state has leaned on the Nagaland Forest Act, 1968, partially updated by the Nagaland Forest (Second Amendment) Act, 2025.

This reform modernizes definitions (e.g., including non-timber produce), equips forest officers with digital tools, raises penalties, and bolsters the Nagaland Forest Development Agency (NFDA) for climate projects and audits. While a step toward accountability, it stops short of mandating Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) for all forest settlements, leaving gaps in transparency, community empowerment, and alignment with national standards like those for Compensatory Afforestation Fund Management and Planning Authority (CAMPA) funds. This is the constitutional trap: Nagaland stands shielded from Delhi but exposed by its own incomplete legal framework, vulnerable in forest conservation, resource governance, and climate finance.

Real Costs of Legislative Absence

The absence of comprehensive state legislation exacts a heavy toll, locking Nagaland’s communities out of opportunities and exposing them to exploitation. First, without legislation fully aligned with national accountability standards, Nagaland risks missing out on environmental funding. From 2019 to 2024, India achieved 85% of its compensatory afforestation targets (1.78 lakh hectares), but states like Nagaland, unbound by the FCA, face indirect barriers to accessing CAMPA disbursements. These funds could have built schools, clinics, or forest restoration projects, but weak state laws hinder eligibility.

Second, resource disputes drain Nagaland’s potential. The state claims oil and gas ownership under Article 371A, yet the Centre asserts control via Central Acts, treating these as Union property. In March 2025, Chief Minister Neiphiu Rio pushed for resuming exploration with a revenue-sharing model, but groups like NSCN-IM warn of community exploitation without stronger state laws. A legislation such as, Nagaland Resource Management Act could secure legal standing and revenue to fund infrastructure, but its absence leaves millions on the table.

Third, predatory external actors exploit the gap. Without robust laws, companies and agents bypass the government, striking deals directly with vulnerable communities for carbon credits or resource extraction. These contracts, often signed without proper consultation, fracture collective rights and erode unity, as seen in ongoing oil exploration disputes.

Finally, customary land titles remain “dead capital.” Banks reject them due to the lack of statutory backing for Village Councils to issue legally valid certificates, despite partial recognitions under the Nagaland Village and Area Councils Act, 1978. This locks community wealth, blocking loans for education, healthcare, or businesses—rendering constitutional land rights economically hollow.

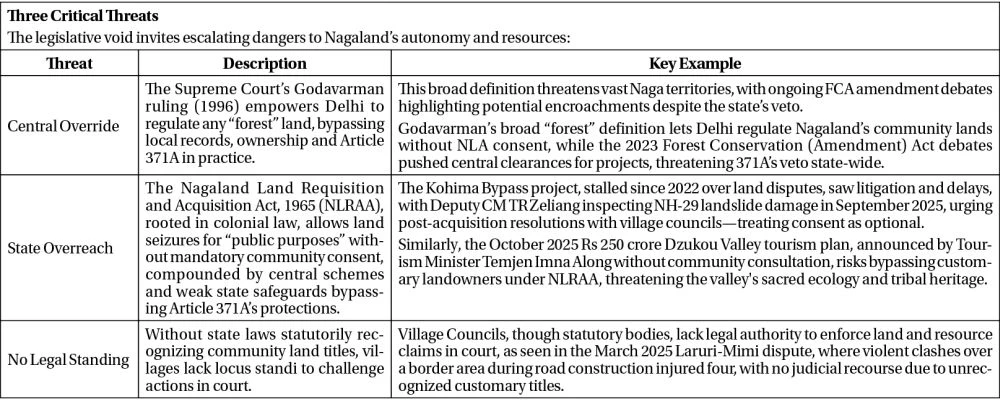

These threats, federal overreach, state bypasses, judicial reinterpretation, and market exploitation, form a vicious cycle, eroding Article 371A’s shield. The Centre’s 2023 push to invalidate Nagaland’s petroleum resolutions and reported non-Naga land acquisitions via banks in 2025, despite NLA safeguards, expose a stark reality: enforcement gaps allow external actors to hollow out Naga autonomy: without proactive laws, external actors and internal gaps could hollow out Naga autonomy. The Supreme Court’s rulings, like Godavarman, loom as potential overrides, while colonial-era laws like the NLRAA enable state-led seizures. With disputes like Laruri-Mimi festering and illegal coal mining persisting, only swift NLA action can secure the future.

The Legislative Solution

To secure Nagaland’s future, the Nagaland Legislative Assembly must overhaul limited frameworks like the Nagaland Village and Area Councils Act, 1978 or the 2025 Nagaland Forest Act Amendment, both of which favour state control over community land rights, by crafting comprehensive state legislation with three community-empowering pillars:

Grant Legal Personality: Empower Village Councils, already statutory under the 1978 Act, with a legal personality to sue and be sued, enabling them to challenge predatory contracts or non-Naga land grabs in court.

Secure Land Titles: Empower Village Councils to issue legally recognized land certificates, accepted by banks, developers, state agencies, and courts, to safeguard community ownership and control against external threats and state overreach.

Mandate Consent: Require Free Prior Informed Consent (FPIC) from customary institutions, including Village Councils, as a non-negotiable precondition for all land and resource projects, ensuring no state or private executive or developer can bypass communities.

Nagaland’s unique status under Article 371A, which safeguards customary laws, land rights, and resource governance, demands that laws integrate traditional practices with modern frameworks, such as land use policies and local governance structures. Drafting these laws must prioritize inclusive, community-driven processes, engaging Village Councils, tribal hohos, women’s groups (to ensure gender-equitable policies), youth (to incorporate innovative and sustainable solutions), legal scholars, and civil society through participatory mechanisms like town halls and workshops. This approach mirrors successful community-driven initiatives, ensuring cultural authenticity and legal rigor while upholding Naga sovereignty against external impositions

A Call to Action

A constitutional right unexercised risks fading into irrelevance. Article 371A’s shield, forged in 1963, stands firm but risks hollowness if Kohima fails to fortify it. The Nagaland Legislative Assembly (NLA) must act before judicial reinterpretation, executive overreach, or market exploitation fills the governance void. The goal is clear: transform the veto, the right not to be overridden, into a guarantee; the right not to be bypassed, through bold legislative authorship. With laws empowering communities via legal standing, secure titles, and mandatory consent for land and resource projects, Article 371A can become a stronghold for Nagaland’s customary land, resource control, and cultural self-determination. The time to act is now. Legislators must summon the vision and political will to enact transformative laws; policymakers and state officials must recognize the peril of inaction and uphold Naga autonomy; and the Naga people must decide—will we accept a fragile status quo, or will we claim and secure the rights guaranteed by Article 371A?