Echu Konyak’s ‘Folktales of the Konyak Nagas’ is a slim volume of tales reflecting migration narratives, animal and human tales in a universe where stones and trees are animate and participatory in the destinies of mankind.

There are enough tales to demonstrate one of the primary tasks served by the folktale – to educate and to teach objective lessons. Such tales have a sad ending and always end with the warning, that is what happens to the children who do not heed their parents’ or grandparents’ or elders’ warnings.

Of great interest are the number of shared migration folktales. The Konyak tell almost the same tale as the Phom and Khiamniungan do of a ‘mighty flood.’ After many days of incessant rain, a universal flood occurred and the only people who survived were the ones who climbed up to the top of Mount Shahen near Changlang village. The story of the flood is told by the Phom, and the tribe uses it as an origin tale pointing to the fact that the flood predated ancestral contact with Christianity. Another shared folktale is the story, ‘The Child swallowed by a Stone,’ which is also told among the Khasis. A nearly identical story is the Zeliang folktale where the elder sister is swallowed by a tree when she is plucking orchids for her younger sister.

The other shared folktale is the one about the great darkness, a story told by the Chang and used by them as the origin of the Naknyulum festival. Obi BihaWangnyak is the great darkness. Echu Konyak’s note says it refers to ‘an incident when a sudden night-like darkness occurred in the middle of the day, and continued for some days.’ Since the darkness continued for many days, people were unable to go to their fields. In the Khiamniungan tale, people escaped to a cave and lived in the cave during the period of darkness in order to avoid being devoured by wild animals. The Rengmas tell a similar tale of darkness inexplicably descending in the middle of the day. Rengma storytellers trace it to the dying of Metishu, the favourite son of God. Shared folktales are intriguing. They provide bridges between the linguistically separated tribes of the Nagas which we should explore as soon as possible.

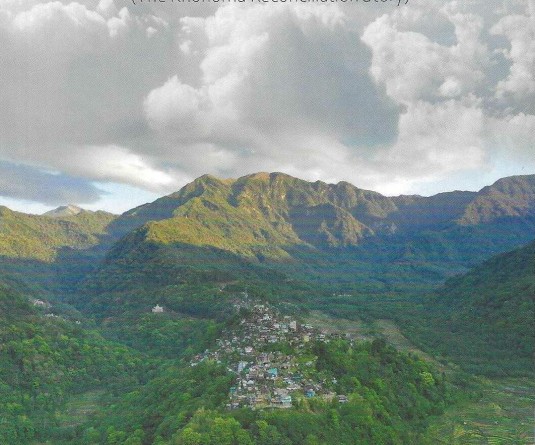

Echu Konyak’s book begins with an origin tale. The Konyaks originally lived atop the mountain Yangnyu Ong, presently in Longleng district. They migrated from Yangnyu Ong after a landslide destroyed their settlement. It is very interesting to see the connection between natural phenomena and taboo violation as brought out in the migration tale in the book. The killing of a spirit animal threatens the survival of the village and the result is the forced migration to another location. The place taboo violations have in village migrations has not been explored sufficiently. Collections of folktales of this category could be a good place to begin.

Konyak Folklore can be seen fulfilling multiple roles, as folklore is always designed to fulfill. It is entertainment, but its purposeful storytelling does not hide the objective lessons it teaches. ‘The quarrelling parents and their son’ effectively teaches parents to be careful of the words they pronounce over their children. Likewise, ‘The widow and her two sons’ teaches children to heed their parents if they want to escape being killed by the enemy.

Folklore is full of origin tales and Echu has collected some samples such as ‘How the leech came to be’ and ‘Why Carp Fish Intestine has Red Bay Scent’ as well as ‘How the Crow became Black.’ Other stories in the same vein are, ‘Why the Dog lives with Humans’ and ‘How the Crab became Flat.’ It is an interesting fact about folklore that it always has an explanatory role to play regardless of is audience. Natural phenomena are explained via storytelling using the logic of the folk. Konyak folktales display sufficient evidence of that. But the volume is certainly not lacking in entertainment. ‘Deweongpüyong -the Spirit Song,’ ‘Princess Nomin and the Crocodile,’ ‘LihaAnghya -the Fairy’ would keep an audience enthralled late into the night around a warm campfire. Animal-human relationships appear in the collection. ‘ShahhuShahmo – the tiger’s Son’ is about a human female courted by a tiger. Interestingly, the Mizo have an abundance of tiger-human tales. The Tigerman is called Keimi in the Zo language. Keimi have many human attributes and seem to be able to change shape at will. In Echu’s story, the tiger names his son, ShahhuShahmo, and the writer tells us that to this day, the village people name their children with the different names that appear in the story of the tiger father. For the Naga tribes, this is the integral role that folklore plays in our daily lives. There are always points where myth and reality cross paths, pause, enmesh themselves and go their own ways carrying parts of each other for all time. Echu Konyak has given what Dr Vizovono Elizabeth calls, ‘a treasure…that needs to be heard, read, told and retold by young and old alike.’