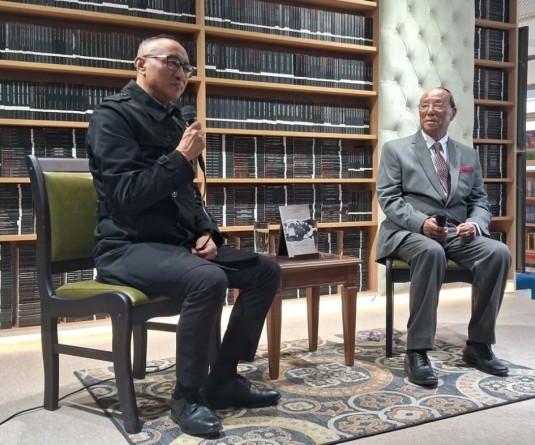

Members of Writers Collective Kohima with Festival Director, Viketuno Rio (5th from R), Peter Modoli of Penguin (R), Publisher of The Morung Express, Aküm Longchari (2nd from R) and others who participated in 'Voices from home' during the closing session of the 3-day “Penguin presents White Owl Literature Festival and Book Fair” on February 19.

Morung Express News

Chümoukedima | February 20

In a world that has often marginalised and restricted Naga narratives and labelled Nagas as ‘savage’, ‘primitive’, and ‘barbaric’, Dr Kevileno Sakhrie on Wednesday evening underscored that the Naga voices are integral “in developing and contributing to a much larger consciousness—literary, social, cultural, political- that need to be recognised and interrogated.”

She was delivering the Way Forward at the closing session of the three-day White Owl Literature Festival and Book Fair on February 19. As part of the closing session, Writers Collective Kohima presented “Voices from Home” featuring readings by Longang Luklem, Vizovono Elizabeth, Aküm Longchari, Inakali Assumi and Emisenla Jamir with a brief introduction by Vishü Rita Krocha.

Stating that “these readings must be received as the voices of individual authors from a society caught in the cross currents of its political and historical inheritances, its personal and communal tragedies, its fractured identities and cultural ambivalences”, she also emphasized that, “it is through such voices that the meaning of human experience from a Naga indigenous perspective can be seen and heard.”

“These portrayals of the big and small stories that make up the everyday life of the Naga and their lived experiences reveal that our literature is out there in the communities, in the realities of ordinary people’s lives,” she remarked.

Today, she said, “the struggle and the slogan of the battle within is to reclaim our identity, our culture, our skies, rivers, trees, and mountains” while impressing upon that “in this, our writers are showing the way by rewriting the literary landscape of Nagaland.”

She went on to say that “their writings combat the internal racism that operates in mainstream national life against our culture, traditions and aspirations that renders the people, culture and politics of these regions invisible.” Through stories that authentically depict the experiences of Naga communities, she said, “they are dismantling colonial and postcolonial ideologies that have disregarded or misrepresented indigenous epistemologies and brought attention to our oral tradition as a strategy to defy cultural homogeneity and assimilation into mainstream narratives.”

By foregrounding lived experiences and value systems that are distinctly different from other cultures, she further commented that, “their narratives act as powerful counter-narratives that confront notions of perceived supremacy by more dominant groups over the so called “margins.””

Henceforth, she emphasised that “outside readers of our works need to be aware of what they bring with them to our stories, such as the false beliefs born of distorted images of our realities, perpetuated by stories told about us, but not by us.”

In this regard, she also underscored that, “by placing the power back into our own hands and enabling us to read value into our own literature on our own terms, our writers are teaching us the Naga way of thinking; they are teaching us to use our imagination, to figure things out for ourselves, to study, to analyse, to frame questions - and also to search out the answers.”

Asserting that this is the indigenous literature of Nagaland, the one where our writers, historians, scholars, researchers and intellectuals are providing ways to reclaim, maintain, and revive epistemologies that have been marginalised, she added that these narratives serve as a catalyst for rebirth in the face of cultural loss.

More significantly, she added, “they provide us with the opportunity to prove to all the world that the marginal can be turned into a vital source of identity and power.”

‘The way forward lies in literary self-determination & literary emancipation’

With the way already paved by our own writers, she remarked that, “the way forward lies in literary self-determination and literary emancipation for ourselves and our communities.” However, while noting that writing is not for everyone, she encouraged emerging writers by saying: “If you have the gift, use it- not just for yourself, but for your tribe, your community, your people.”

She also reminded that writing is power and that, like all power, it can be used for good or bad. Emphasising that to be a writer comes with responsibilities, she further maintained that, “to be an indigenous Naga writer is to be part of a legacy of struggle and survival, of determination to speak truth into a world that has long silenced us.”

“So take care never to write in any way that diminishes your people but always to strengthen their souls”, she advised. In this connection, she also posed, “what is the role of the reader in this equation? How much responsibility do we bear in this journey towards literary emancipation? What kinds of responsibilities might we have as witnesses to these stories of pain, healing, and transformation?”

Pointing out that an important aspect of indigenous storytelling is accountability, she underscored that, “for a work to be transformative, the author must feel a sense of intellectual and even spiritual responsibility to their readers.”

In turn, she said, “we, as readers need to engage with these stories from the same place of honesty and openness that they flow from.” “Let them soak in, take time to process the words”, she expressed while maintaining that, “for indigenous peoples like ourselves, stories are open-ended processes for speaking reclamation and resurgence, dialogue and contestation; they are part of a cycle of renewal and recreation and thereby, a way to go forward.”