Students from GPS Ward 13, Landmark Colony, Dimapur, being taught at a shed in a children’s park. (Morung Photo)

Morung Express News

Dimapur | April 3

Dimapur | April 3

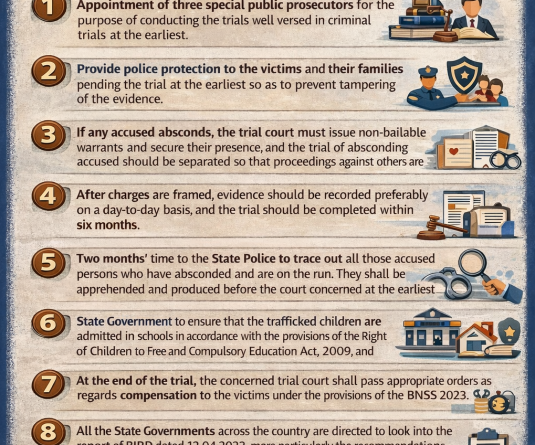

If you thought the peripheries of Nagaland remain outside the purview of the Right to Education, the story of 75 students and 10 teachers of a Government Primary School (GPS) in Dimapur will leave you thinking more. For over a month now, they have been forced to make “school” of a tin shed in a “children’s park” in the wind, rain, and sun.

In 2010, the GPS Ward 13, Landmark Colony (Dimapur), was set up in a cylindrical structure out of World War II. Sources suggest it was constructed as a warehouse for arms and ammunition by the British. When the colony (village) Councils concerned (Landmark colony, Midland colony and Residency colony) decided to shift the 75 currently enrolled students from the warehouse to a new structure, problem began, leading to the students and teachers “schooling” in a children’s park at Landmark colony.

“We were directed by the three colony councils to shift the school to a newly constructed structure on February 25 (2014),” says teacher-in-charge of GPS Ward 13, Ahoi Sema. “We wrapped everything up, and even shifted all papers, benches etc. to the new premise immediately. On February 26, when we tried to take the children to the new structure, we found armed IRB cadres there—the district administration was obstructing the students from entering the new building,” he informs. In order to save the children of “psychological damage” from guns being pointed at them, the teachers kept them away from the new building at Landmark colony.

As of April, “we’re in the middle of nowhere,” say teachers Tsuktinungla, Rebikha and Alemsenla. Since February, they have been forced to conduct “learning exercises” at a children’s park, a sandy ground opposite the old premise. There were no toilets or drinking water facilities before; they are obviously missing now—a neighbour lent his toilet to the students and teachers the last four years.

“It is very windy, and the harsh sun does not permit us to take more than two hours of classes,” informs teacher Tsuktinungla Jamir. “We give them homework and conduct learning exercises. We are all falling sick from the excessive dust—influenza, dust allergies—and dousing their curiosity at an age they could be learning. But how can we teach? How can they learn?” she wonders.

The land that the colony councils decided to make the new structure on turned out to be owned by the Government of Nagaland’s Public Works Department (Roads and Bridges, and Housing). Half of this land has been allotted, as per sources, to the ruling regional party of Nagaland. Another part of the rest of it has been allegedly “encroached” by a private entity. The remaining, according to sources, has been set aside by the PWD (R&B&H) for a planned “Phase III rental house construction.” This is where the new structure for the GPS was constructed, finding itself in an “illegal” zone.

“We have been pursuing the allotment of this empty piece of land for the school with the highest authorities for the past four years,” reveals chairperson of School Managing Committee of the colony, Wapang Aier, but to no avail.

The Naga Students’ Federation (NSF) and the Dimapur Naga Students’ Union stepped in to help in early March, 2014. The NSF wrote and spoke to the Commissioner & Secretary (Works and Housing), Chief Engineer of the department concerned, Parliamentary Secretary (Housing) and the Minister of Roads and Bridges. “We are awaiting a positive response from the government in regard to the letter we submitted to the Parliamentary Secretary (Housing) on March 25 on the said matter,” informs NSF president, Tongpang Ozukum. The NSF also asked the PWD (R&B&H) to “reconsider their decision to build the Phase III rental house construction” in the interest of education. They have been informed that the matter will be dealt with “after election.”

While there is a question of “legally not right” occupation of land for the school, the question is why do students have to bear the brunt of “legality”?

It doesn’t help that children at the school are from poor and peripheral backgrounds. Their textbooks came late, some are still carrying on with old school uniforms, and now this. “How can free and compulsory education be imparted without a school building?” questions Ahoi Sema, wondering what meaning the Right To Education Act, passed in April 2010, has for these children.