Dr. Arkotong Longkumer

The University of Edinburgh

Dr. Dolly Kikon

The University of Melbourne

During the lockdown in 2020 due to the global pandemic, the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, England, undertook a major reform. They decided to overhaul insensitive displays that highlighted the violent history of colonialism and imperialism. The Pitt Rivers Museum recognised that their collections have propagated harmful colonial stereotypes of cultures across the world. This statement of intent is reflected in the Museum’s ‘Committed to Change’ where it says that they ‘aim to be part of a process of redress, social healing and the mending of historically difficult relationships’.[2] In order to portray cultural objects in an ethically sensitive manner, the Pitt Rivers Museum has recognised that decolonising the museum and prioritizing reconciliation and co-curatorship with source communities is a matter of urgency.

It was in this spirit of decolonization and healing, that we started a dialogue and reflective journey with the Pitt Rivers Museum. As Naga anthropologists we are aware that they have the largest collection of Naga material culture in the world (around 6466 items), including the human remains of our ancestors. With an atmosphere of openness, respect, and a desire to include Naga community members –elders, researchers, church and civil society – through interviews and collaborative discussions, we put together an exploratory research project. In 2020, a Naga Research Team was formed, comprising researchers from the Naga ancestral homelands working in partnership with the Pitt Rivers Museum, and started the initial phases of the project.

Inside the Pitt Rivers Museum, used with permission.

Our aim is to address issues surrounding the repatriation of around 213 ancestral remains currently housed in the Pitt Rivers Museum. Their descriptions, spread over numerous pages of excel sheets, provide a glimpse into the expanse of the machinations of the British Empire – from conquering, to administrating, to collecting, and to ruling– a process that remains undiminished and indeed unfinished. As Naga anthropologists engaged in this introspective engagement of reparation and healing, we are aware that the process will generate deep emotions including grief and anger, as well as open historical trauma for the Naga people. For more than 100 years, museums across Europe have displayed Naga objects as exotic and primitive, taken away as souvenirs and under duress during colonial expeditions, a fact that exposes the harsh realities of imperialism, and their contemporary resonances.

The Naga ancestral remains collection in the Pitt Rivers Museum consists of human skulls and bones, and human hair attached to various cultural items including basketry, spears, shields and ornaments. The provenance of these remains is unclear. Some clearly state that they were confiscated by British administrators from Naga villages, while others were taken as loot during the violence that ensued. The labels have limited information or explanation and much of people’s histories and their encounters with colonialism have been undocumented and in fact erased. For instance, one of the entries on a Naga skull has the following, obscure description:

‘Trophy skull of a Konyak woman of Kamahu mounted with mithan horn taken at Yacham by an Ao Naga. [This was taken] from him by Mr Hutton [a British Administrator] when the village was burnt by the Government, March 1922’.

Central to the partnership between the Pitt Rivers Museum and Naga Research Team is a shared vision to decolonize dominant frames of knowledge and recognize the violence of colonialism. As we continue our exploratory research and dialogue, we are learning how the meaning of decoloniality involves recognizing the Naga people’s history as one of colonization and loss. Indeed, the Naga people will have a remarkable opportunity to reflect on the future of their ancestral remains in the Pitt Rivers Museum and other museums in Europe and beyond.

The British started administering the Naga Hills, as it was known then, in 1832 to protect the burgeoning tea trade in Assam, a product consumed by millions in Britain and throughout their extensive Empire. In 1865, an article in the Pioneer justified British rule over these ‘savage’ tribes because they were a danger ‘to the cause of tea’. While the lucrative tea trade had to be protected at all costs, it also allowed the British to engage in civilising missions. This included inviting the American Baptist Foreign Mission Society (1871-1955), who were in Myanmar missionising the Karen people, to enter the Naga Hills and begin the process of conversion. Thus started the colonial strategy of the bible and the flag – Christian conversion, alongside steady territorial gains so that by around 1912 the Naga Hills District became a province of Assam and remained so until Indian independence in 1947.

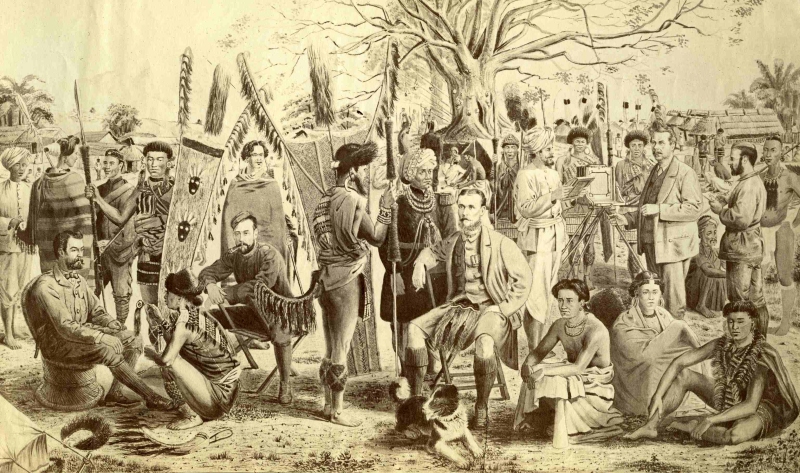

This period of British colonialism was particularly violent. There were numerous military raids to suppress the recalcitrant Nagas, which included burning villages as collective punishment, and the loss of lives, not to mention the vast troves of material culture burnt into the embers of history. When British colonial power was largely consolidated, visual depictions often portrayed the Nagas as exotic but now ‘tamed’ under the rule of the British Raj, who were viewed as humane, orderly and enlightened.

300_442-1. Photograph taken from a large sepia picture by Woodthorpe (all portraits taken from actual sitters). These include Captain Badgley, Lt. Ridgeway, Captain J. Butler, Dr R. Brown, R.G. Woodthorpe (standing second from right) and 11 named Nagas. Suivly Camp, Lak Nuti, Rengma Naga Village, season 73-74, c. 1874 © RAI

Historically, the proliferation of images of the Nagas filled the British imagination with depictions of the frontiers of the Empire. According to Andy West’s book Museums, Colonialism and Identity: A History of Naga Collections in Britain, the Nagas were mostly represented in ceremonial clothes with their headdresses, spears, and dao (hacking knife). Reams of pages were dedicated to the discussion and knowledge production of the Nagas from 1822-1920, leading J.H. Hutton (1885-1968), a seasoned British administrator, to list over 400 publications related to them. One of the chief architects of the Pitt Rivers Museum, Henry Balfour (1863-1939), urged colonial administrators to collect as much material culture as possible, or as he put it ‘If we aim at equitable administration of subject races, the chief essential is close investigation of their indigenous culture’. That legacy is now inherited by the Pitt Rivers Museum, along with collections at the British Museum, the Cambridge University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, and the Horniman Museum, and other smaller collections scattered in over 50 museums all over Britain.

During Indian Independence in 1947, the Naga areas were split between India and Myanmar, with the boundaries marked arbitrarily by Prime Ministers Jawaharlal Nehru and U Nu, based loosely on British administrative demarcations. The British fragmented the Naga ancestral homeland as a result of administrative bureaucracy and this continued unabated when the Indian and Burmese governments began their rule. This legacy of British colonialism, carried over into the Indian state to divide and rule, with continued violence inflicted with impunity is a tragic story of our times. Not only did this separate the Naga lands but divided the Nagas in India internally into Nagaland, Manipur, Arunachal Pradesh and Assam. The Naga Hills (and) Tuensang Area is now the state of Nagaland which was formed in 1963.

The Naga movement for sovereignty was led by the Naga National council (NNC). The NNC later fractured into several groups one of which led to the formation of the National Socialist Council of Nagaland. The essence of the Naga movement was led by their desire to be left alone and not to be included in the Indian Union. We provide this context to highlight the complex history of this region and the effects of colonialism.

The injustice and colonial violence that divided the Naga ancestral homelands did not appear in the administrative, missionary, and ethnographic writings of the time. Even some Indian scholars in post-independent India writing on the Nagas have ignored the divisiveness of colonialism and structural violence perpetuated by the new nation-state. In contrast, our ongoing dialogue and research framework with the Pitt Rivers Museum is to centre Naga heritage and history, focused on framing an Indigenous pedagogy of healing and reparation, where the Naga people’s voice must be central to how we engage with the Naga collection. Given that the Naga collection at the Pitt Rivers Museum has remained largely inaccessible to the Naga community, the experiences of colonialism are often treated as archival data where issues of ethics and community consent have been ignored and where access to information have been given to a privileged few. We believe that re-crafting the story of the Naga collection rests with the Naga people.

Any repatriation of Naga ancestral remains bears the additional challenge of recognising the complex geo-political boundaries of the Naga ancestral homelands in contemporary India and Myanmar. One of the first questions we encountered was: who do we repatriate the ancestral remains to? Where does one start? During the first few months, we contacted various Naga individuals to discuss these issues. Some were open to bringing ancestors back to their communities, so they can be reburied, while others were more apprehensive. What sort of burial will they be given? Would it be a Christian one? How do we ascertain if pre-Christian rituals would be more apt, and how might these traditions, now largely suppressed, enable the dead to be honoured? Would it be more appropriate to collectively mourn ancestors through creating a national memorial? Some individuals were more direct in their responses. If these remains were part of war and their heads taken as trophies (before the British looted them), then, there is a tradition of not asking for them back.

The answers to these questions are still uncertain. This research project is just the beginning of our quest to understand the untold stories, events and memories that remain buried. We have inherited the cultural trauma of colonialism that previous generations rarely spoke about. Would a demand for a public apology from the British government, as some have voiced, begin to heal the wounds of colonialism? The ongoing research collaboration is an opportunity for us to understand the past through the lives of our ancestral remains even as we continue to discover and add new items with the support of the museum curators. The work ahead of us is challenging, but as a research team, we are committed to documenting the stories of the Naga ancestral remains and the journeys they have undertaken from their homes in the Naga areas to entombed spaces inside museums. Like vast jigsaw puzzles, there are still many pieces to fall into place.

The ‘healing of the land’ is a sentiment that surfaces over and over again in our many conversations with Naga individuals and communities. Engaging with the ancestral remains and putting them to rest means a renewal of the land, and an understanding of the tempestuous historical moments that have come to define the Naga people. This is a task that not only requires reflection about the past, but also a hope for a future that younger generations can inherit, a land where our ancestors are laid to rest and where healing and reconciliation can begin.

We realise that this undertaking is a collective and shared one – and we must learn from those who have gone before us. Along the way we have found support and guidance from a native Hawai‘i activist, Edward Halealoha Ayau, who has been working for over 30 years with various museums and institutions to repatriate iwikūpuna (ancestral Hawaiian skeletal remains), moepū (funerary possessions) and meakapu (sacred objects).[3] Similarly, Return, Reconcile, Renew (RRR) has provided us with databases and training with regard to the repatriation of ancestors, a process they have begun in the context of Aboriginal Australians.[4] These partnerships highlight the strength of Indigenous peoples’ networks and the willingness and courage they demonstrate through the sharing of knowledge.

Indeed, the realities of colonialism are widespread. But the movement for justice and decolonization persists. Cultural objects belonging to source communities stolen during British colonialism have received significant attention in recent times. The controversy over the Benin Bronzes and the decision by Cambridge and Aberdeen Universities to return them to Nigeria has generated important debates regarding restitution and the broader questions around colonialism. Like many of these instances demanding restitution, the Naga people’s case requires that we understand the immense violence and trauma that they continue to experience. Reconciliation and healing of the land are not simply tropes that need discussion. They need to be embedded in a process where the community takes ownership and custodianship, and through that, hopefully, there is a more humane approach towards decolonisation and justice.